Weekly Reading Log Total Number of Minutes Read This Week

This is the 2nd entry in the Teaching Leader's Guide to Reading Growth, a vii-part series near the human relationship betwixt reading practice, reading growth, and overall student achievement.

In our last post, we examined how reading practice characteristics differ betwixt persistently struggling students and students who get-go out struggling simply end up succeeding—and how potent reading skills are linked to high school graduation rates and college enrollment rates.

Nonetheless, it'southward not just struggling readers who could benefit from more reading exercise. A study of the reading practices of more than nine.9 million students over the 2015–2016 schoolhouse twelvemonth found that more than one-half of the students read less than xv minutes per day on average.1

Fewer than one in 5 students averaged a one-half-60 minutes or more of reading per twenty-four hours, and fewer than one in three read betwixt 15 and 29 minutes on a daily footing.

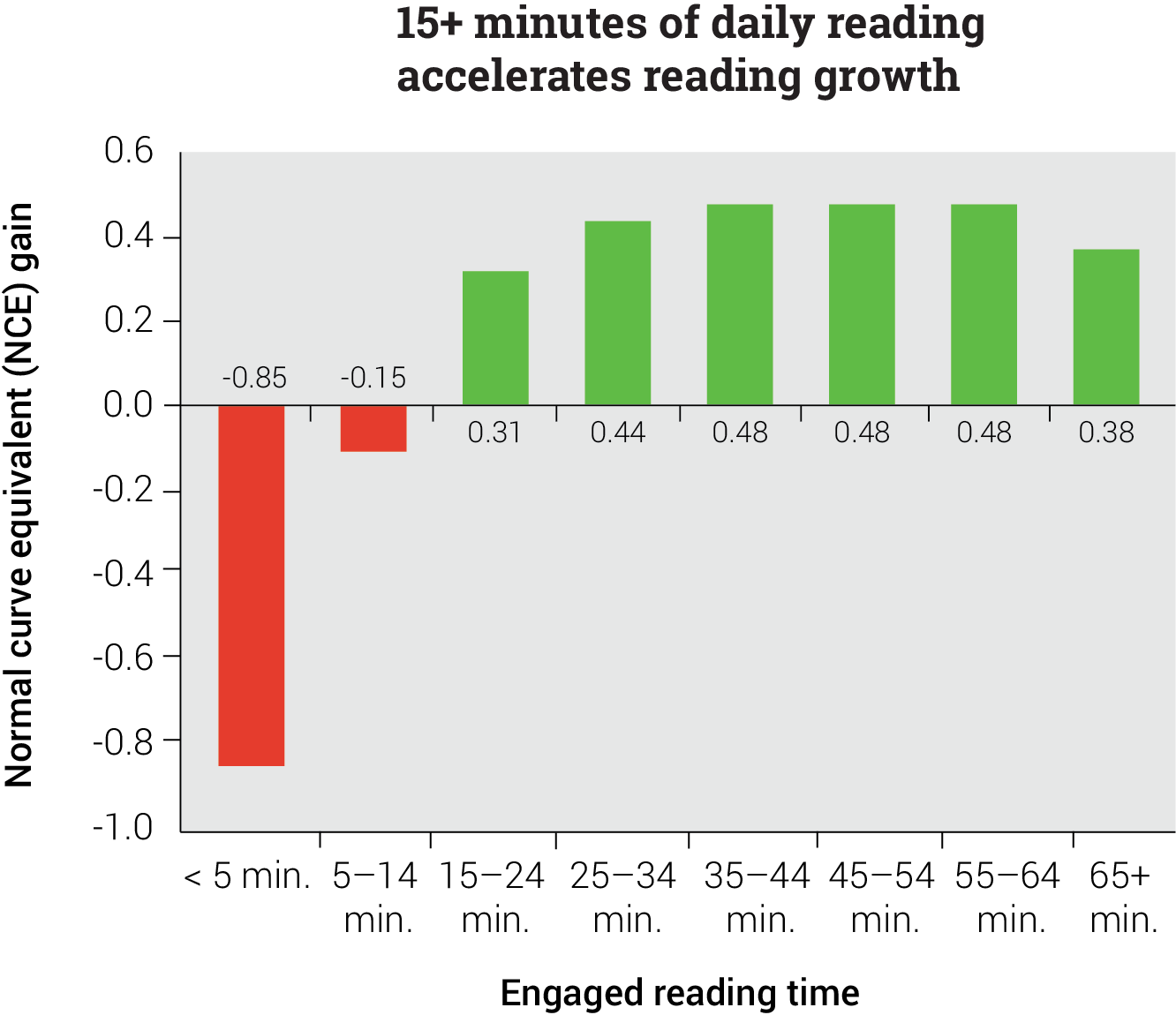

The trouble is that fifteen minutes seems to be the "magic number" at which students start seeing substantial positive gains in reading achievement, nevertheless less than one-half of our students are reading for that amount of fourth dimension.

xv minutes seems to be the "magic number" at which students starting time seeing substantial positive gains in reading achievement; students who read just over a one-half-hour to an hour per day meet the greatest gains of all.

An assay comparison the engaged reading time and reading scores of more than than 2.two million students found that students who read less than five minutes per twenty-four hour period saw the everyman levels of growth, well below the national boilerplate.2 Even students who read v–14 minutes per solar day saw sluggish gains that were below the national average.

Only students who read xv minutes or more than a day saw accelerated reading gains—that is, gains higher than the national average—and students who read just over a one-half-hour to an hr per day saw the greatest gains of all.

Although many other factors—such as quality of didactics, equitable access to reading materials, and family background—also play a role in achievement, the consistent connexion between time spent reading per day and reading growth cannot be ignored.

Moreover, if reading practice is linked to reading growth and accomplishment, and so it follows that low levels of reading practice should correlate to low levels of reading performance and high levels of reading practice should connect to loftier levels of reading performance. This pattern is precisely what we see in educatee exam information.

Strong connections betwixt reading do and achievement

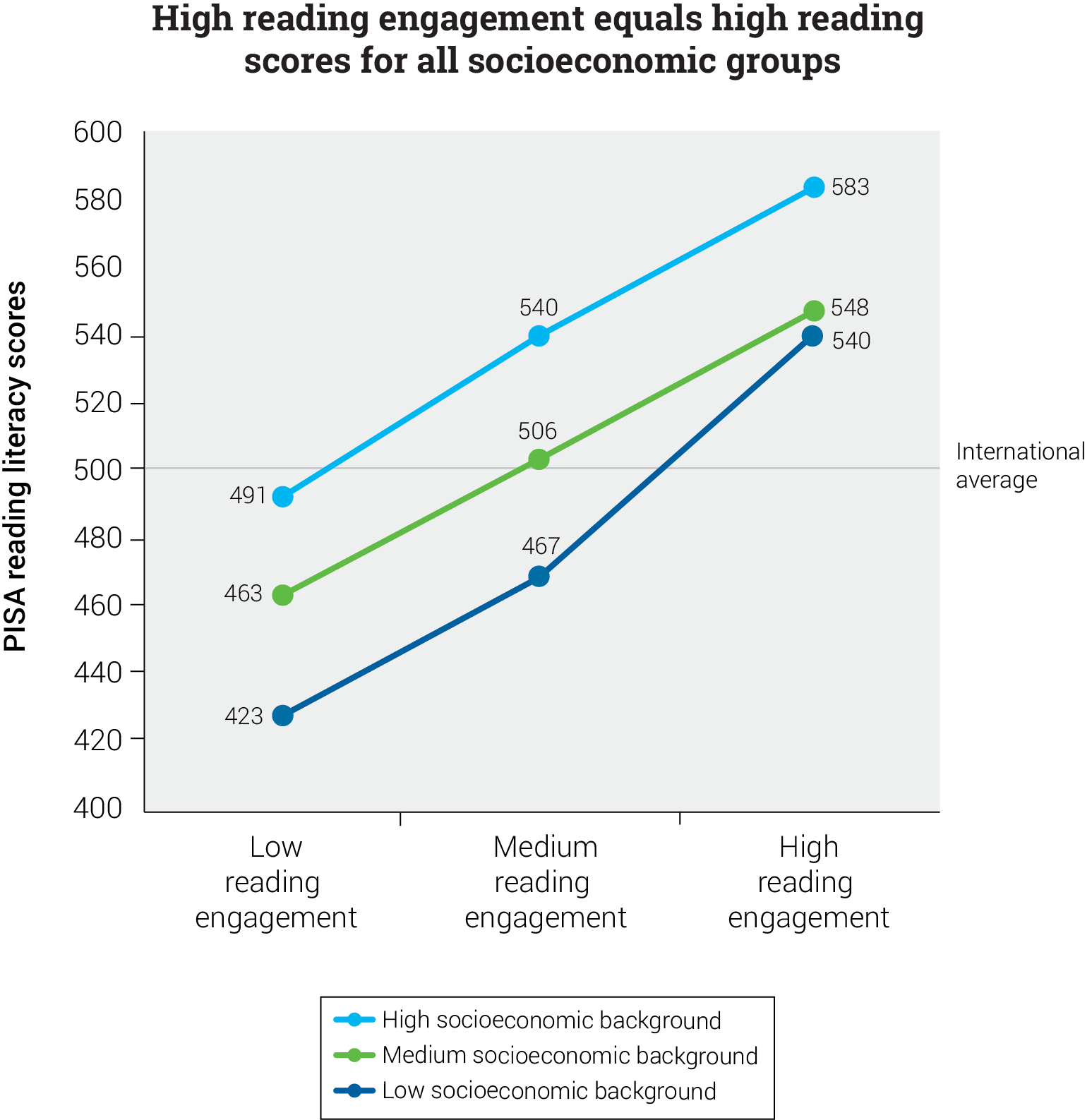

An analysis of more 174,000 students' Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores revealed that connection between reading engagement and reading performance was "moderately strong and meaningful" in all 32 countries examined, including the United states of america.three On average, students who spent more time reading, read more diverse texts, and saw reading every bit a valuable action scored higher on the PISA's combined reading literacy scale.

The study too plant a student's level of reading engagement was more highly correlated with their reading achievement than their socioeconomic status, gender, family construction, or time spent on homework. In fact, students with the everyman socioeconomic background but high reading engagement scored improve than students with the highest socioeconomic groundwork just depression reading engagement.

Overall, students with high reading appointment scored significantly above the international average on the combined reading literacy scale, regardless of their family unit background. The opposite was also true, with students with low reading engagement scoring significantly below the international boilerplate, no matter their socioeconomic status.

The authors suggested that reading practice can play an "important office" in endmost achievement gaps betwixt different socioeconomic groups. Frequent high-quality reading practice may help children compensate for—and fifty-fifty overcome—the challenges of beingness socially or economically disadvantaged, while a lack of reading practice may erase or potentially reverse the advantages of a more than privileged groundwork. In brusk, reading do matters for kids from all walks of life.

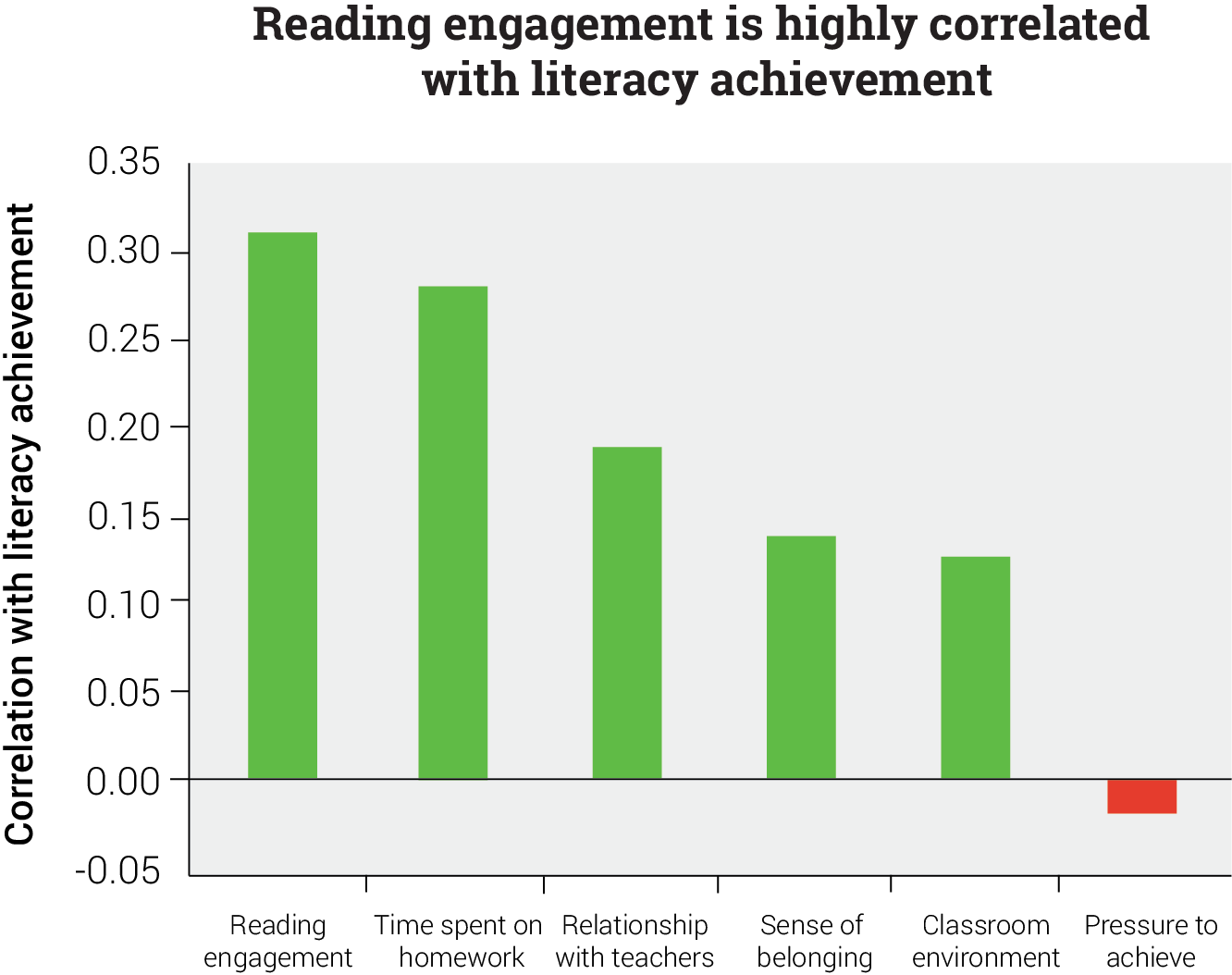

For students inside the United States, reading practice may not simply be more of import than socioeconomic condition—it may also be more important than many school factors.

Looking at only American students' PISA scores, we run into that reading engagement had a college correlation with reading literacy accomplishment than time spent on homework, relationships with teachers, a sense of belonging, classroom environment, or even pressure to achieve (which had a negative correlation). In addition, a regression assay showed accomplishment went up across all measures of reading literacy performance when reading appointment increased.

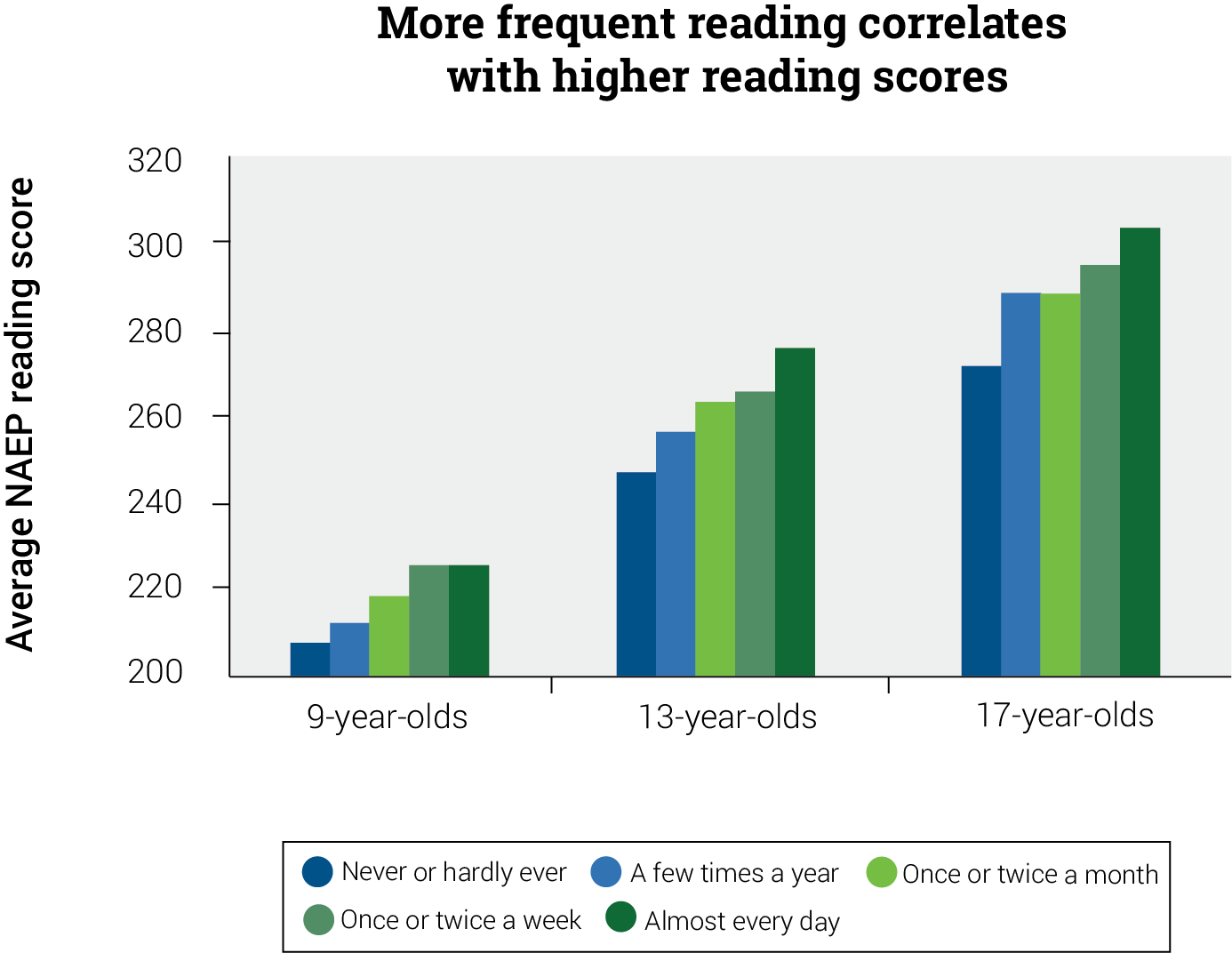

Although the PISA only assesses 15-twelvemonth-olds, similar patterns can exist seen in both younger and older American students. In 2013, the National Center for Pedagogy Statistics (NCES) compared students' National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading scores with their reading habits.4 For all age groups, they found a clear correlation betwixt the frequency with which students read for fun and their average NAEP scores: The more frequently students read, the higher their scores were.

What is particularly interesting near the NAEP results is that the correlation between reading frequency and reading scores was true for all age groups and the score gaps increased across the years. Amid 9-year-olds, there was merely an 18-point deviation between children who reported reading "never or inappreciably ever" and those who read "about every day." By age 13, the gap widened to 27 points. At historic period 17, it farther increased to 30 points.

This seems to run opposite to the usually held wisdom that reading practise is most important when children are learning how to read but less essential one time key reading skills have been acquired. Indeed, we might fifty-fifty hypothesize the opposite—that reading practice may abound more important as students move from grade to grade and come across more challenging reading tasks. Until more inquiry either confirms or disproves this possible explanation, it is nothing more than a guess, just an interesting one to consider notwithstanding.

However, what is clear is that reading practice is decreasing amongst all historic period groups, with the nearly dramatic decreases among the very students who may demand it the about.

Troubling declines in reading exercise

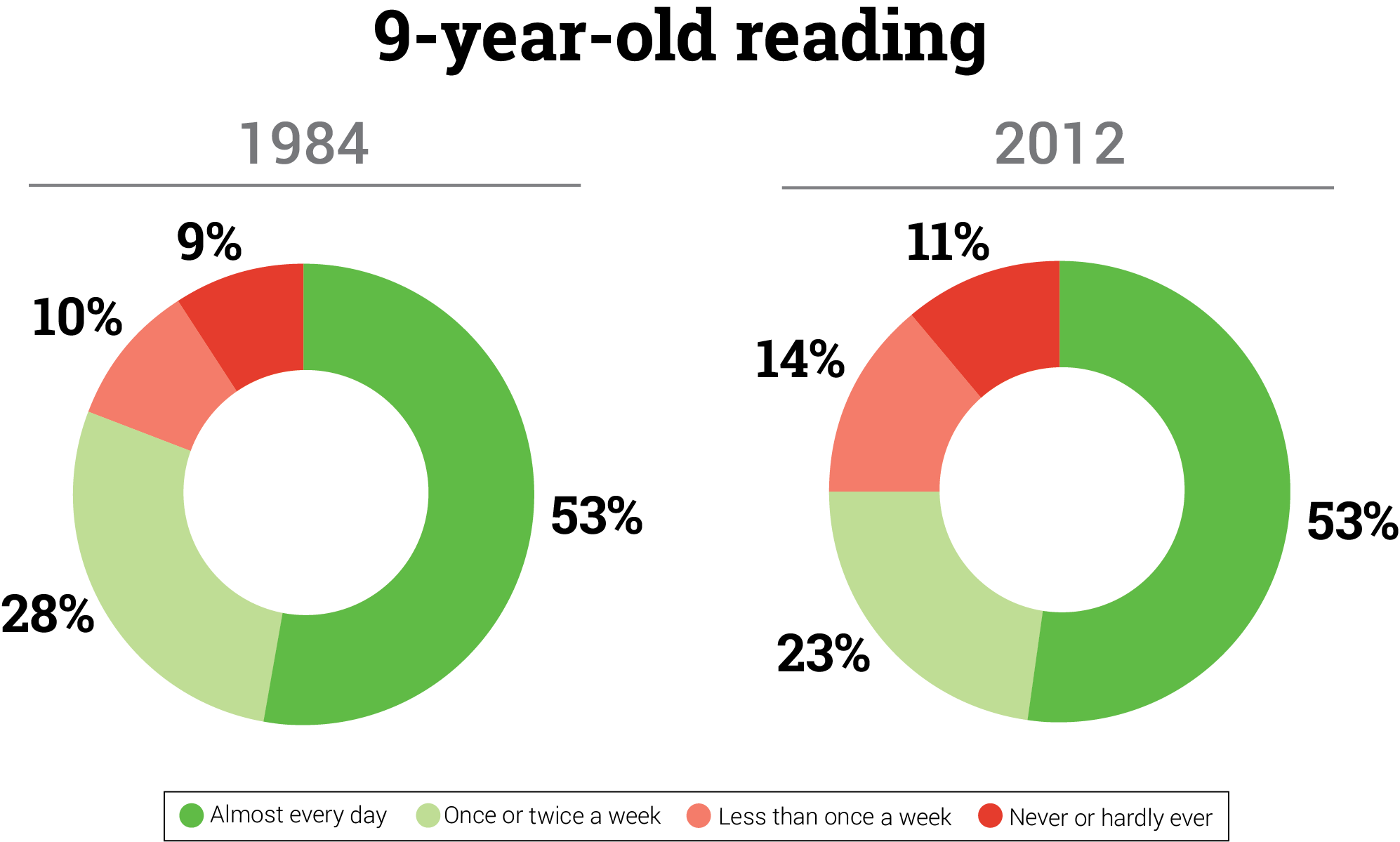

Over the last iii decades, reading rates have dramatically declined in the United states of america. In 1984, NAEP results showed the vast majority of ix-twelvemonth-olds read for fun in one case or more per week, with more than than one-half reporting reading almost every 24-hour interval. Only one in five reported reading ii or fewer times per month. By 2012, 25% of all 9-year-olds were reading for pleasure fewer than 25 days per yr.5

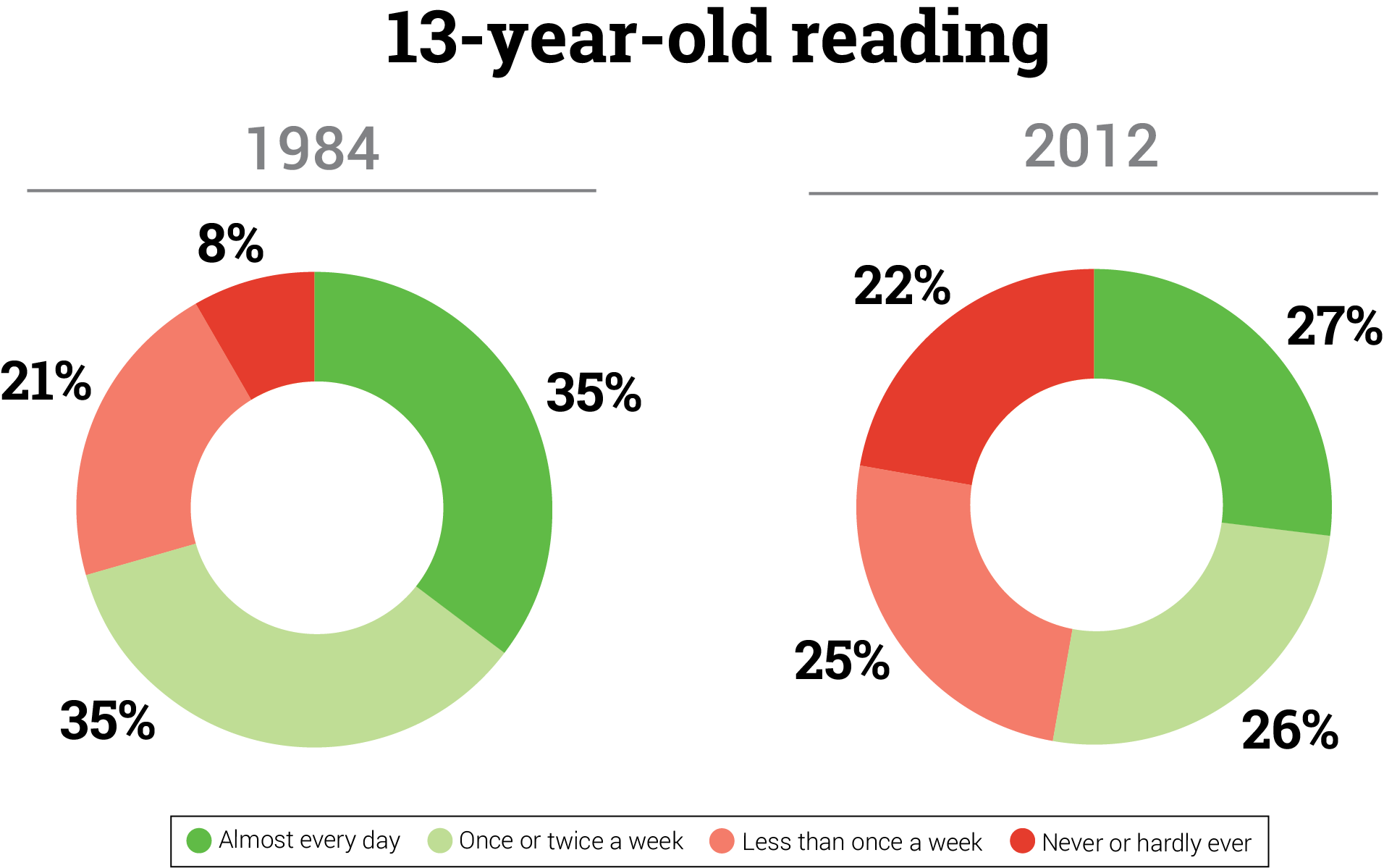

For older students, the drop is even more precipitous. In 1984, 35% of xiii-year-olds read for fun almost every twenty-four hours, and some other 35% read ane or two times per week—in total, more than two-thirds of 13-year-olds reported reading at to the lowest degree once a week. In 2012, virtually one-half read less than once a calendar week.

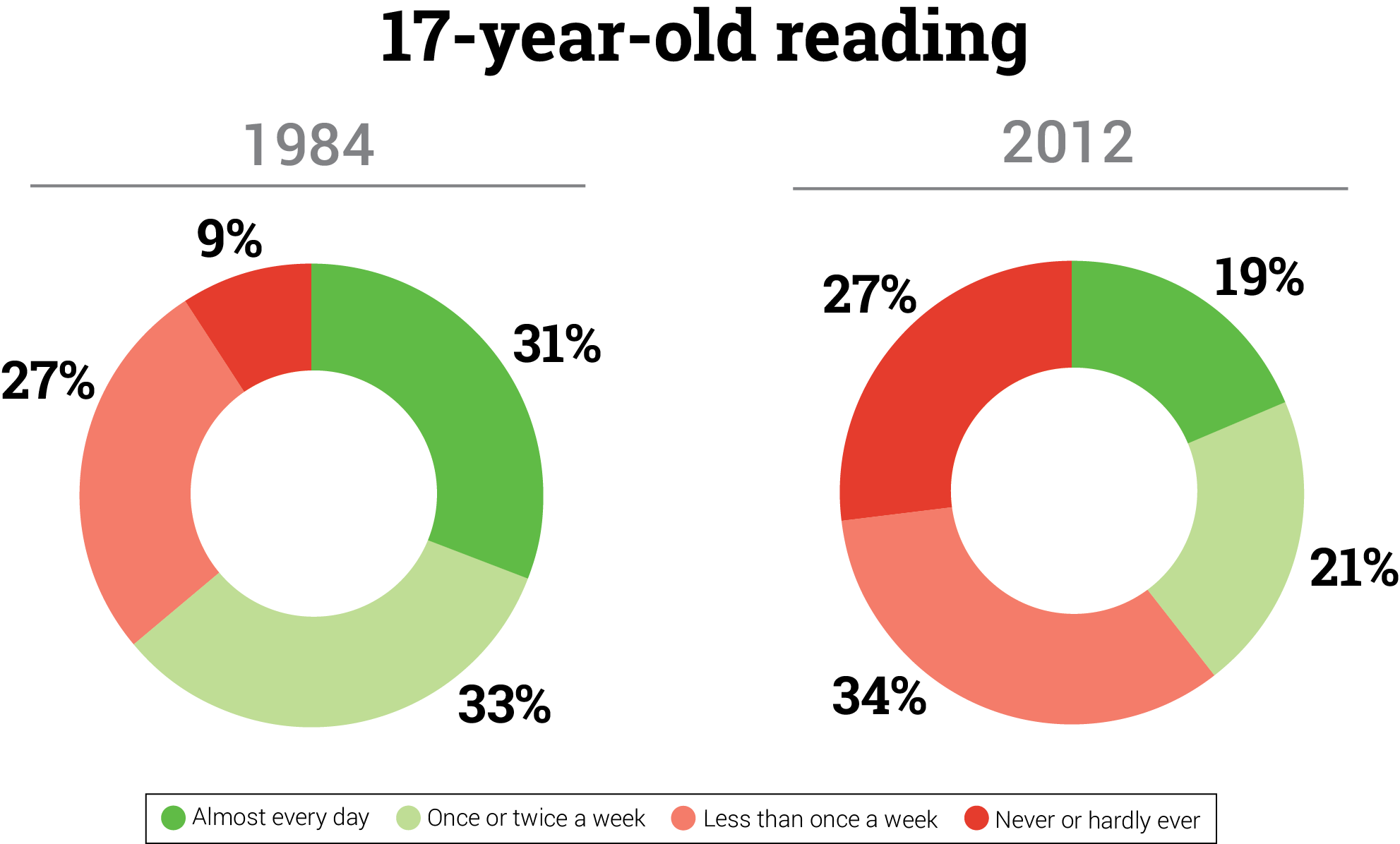

Among 17-yr-olds, the per centum reading most every mean solar day dropped from 31% in 1984 to only 19% in 2012, while the percentage who read for fun less than once a week rose from 36% to 61%. The number of 17-year-olds reporting reading "never or hardly ever" really tripled.

And the decline in reading is not due to students spending more than time on homework in 2012 than in 1984. During the same time period, the percentage of students who reported spending more than an hour on homework really declined.

In 1984, nineteen% of ix-yr-olds, 38% of 13-year-olds, and 40% of 17-year-olds reported spending an hour or more on homework the day prior to the NAEP. In 2012, those numbers had dropped to 17% for 9-year-olds, 30% for xiii-twelvemonth-olds, and 36% for 17-yr-olds.

Why are we seeing the greatest gaps and the greatest declines in the oldest students? Although many different factors are likely at play, one of them might be that the effects of reading practice are cumulative over a student's schooling, especially when it comes to vocabulary.

The long-term furnishings of reading exercise

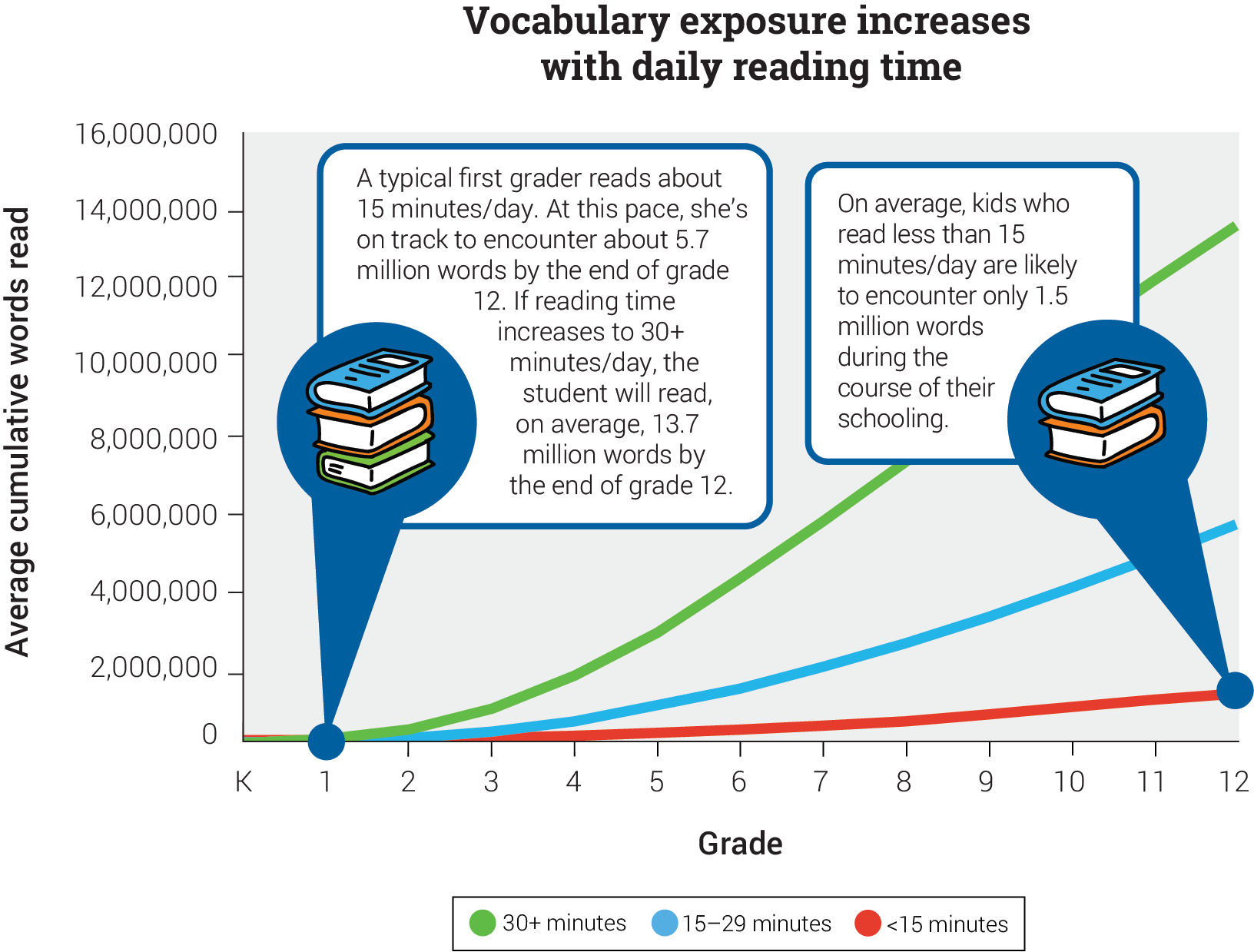

What's the difference between kids who read more than 30 minutes per day and those who read less than 15 minutes per day?

Twelve million.

Between kindergarten and twelfth grade, students with an boilerplate daily reading time of xxx+ minutes are projected to encounter 13.7 one thousand thousand words. At graduation, their peers who averaged less than 15 minutes of reading per day are likely to be exposed to only ane.5 1000000 words. The departure is more than 12 1000000 words. Children in between, who read 15–29 minutes per mean solar day, will encounter an boilerplate of 5.7 1000000 words—less than one-half of the high-reading grouping just nearly four times that of the low-reading grouping.1

Some researchers estimate students learn one new word of vocabulary for every thousand words read.6 Using this ratio, a student who reads just one.5 meg words would acquire only 1,500 new vocabulary words from reading, while a student who reads thirteen.seven million words would learn 13,700 new vocabulary terms—more than nine times the amount of vocabulary growth.

This is peculiarly important when nosotros consider that students can learn far more words from reading than from straight instruction: Even an aggressive schedule of 20 new words taught each calendar week will result in only 520 new words by the end of the typical 36-week school year. This does not mean that reading practice is "meliorate" than direct instruction for edifice vocabulary—direction didactics is primal, but teachers can just practise so much of it. Instead, we ask educators to imagine the potential for vocabulary growth if direct education, structural analysis strategies, and reading practise are all used to reinforce one another.

Vocabulary plays a critical part in reading accomplishment. Research has shown that more than half the variance in students' reading comprehension scores can be explained by the depth and breadth of their vocabulary knowledge—and these two vocabulary factors tin can fifty-fifty be used to predict a student's reading functioning.seven

Nosotros can come across the human relationship between vocabulary and reading accomplishment conspicuously in NAEP scores, where the students who had the highest average vocabulary scores were the students performing in the top quarter (above the 75th percentile) of reading comprehension. Similarly, students with the lowest vocabulary scores were those who were in the bottom quarter (at or below the 25th percentile) in reading comprehension.viii This means those boosted 12 million words could potentially have a huge touch on on student success.

So what are nosotros to do, when reading practice is so clearly connected to both vocabulary exposure and reading achievement, but not plenty students are getting enough reading practice to bulldoze substantial growth?

The answer seems clear. We demand to brand increasing reading practice a acme priority for all students in all schools. Making reading practice a system-wide objective may be 1 of the well-nigh important things we tin practice for our students' long-term outcomes, particularly when we combine information technology with high-quality instruction and effective reading curricula. It is time to put equally much focus on reading practise every bit nosotros exercise on school culture, student-educator relationships, and socioeconomic factors.

Notwithstanding, not all reading exercise is congenital the same. Quantity matters, but so does quality. In the next post in this series, we explore how you tin can ensure your students are getting the well-nigh out of every infinitesimal of reading practice.

To read the next postal service in this series, click the imprint below.

References

1 Renaissance Learning. (2016). What kids are reading: And how they grow. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

2 Renaissance Learning. (2015). The research foundation for Accelerated Reader 360. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

3 Kirsch, I., de Jong, J., Lafontaine, D., McQueen, J., Mendelovits, J., & Monseur, C. (2002). Reading for alter: Performance and engagement across countries: Results from PISA 2000. Paris, France: System for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

4 National Heart for Education Statistics. (2013). The nation's report carte: Trends in academic progress 2012 (NCES 2013 456). Washington, DC: U.Southward. Section of Education Institute of Didactics Sciences.

five National Center for Pedagogy Statistics. (2013). Table 221.xxx: Average National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading scale score and percentage distribution of students, past age, corporeality of reading for schoolhouse and for fun, and time spent on homework and watching TV/video: Selected years, 1984 through 2012. Digest of Instruction Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Section of Educational activity Institute of Pedagogy Sciences. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_221.30.asp

half dozen Stonemason, J.M., Stahl, S. A. , Au, K. H. , & Herman, P. A. (2003). Reading: Children'south developing knowledge of words. In J. Alluvion, D. Lapp, J. R. Squire, & J. M. Jensen (Eds.), Handbook of inquiry on instruction the English linguistic communication arts (2d ed., pp. 914-930). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

7 Qian, D. D. (2002). Investigating the Relationship Between Vocabulary Knowledge and Academic Reading Performance: An Assessment Perspective. Language Learning, 52(3), 513-536.

eight National Center for Teaching Statistics. (2013). 2013 Vocabulary report. 2013 Reading assessment. Washington, DC: U.Southward. Department of Education Plant of Education Sciences.

Source: https://www.renaissance.com/2018/01/23/blog-magic-15-minutes-reading-practice-reading-growth/

0 Response to "Weekly Reading Log Total Number of Minutes Read This Week"

Post a Comment